Share this article on:

Powered by MOMENTUMMEDIA

Breaking news and updates daily.

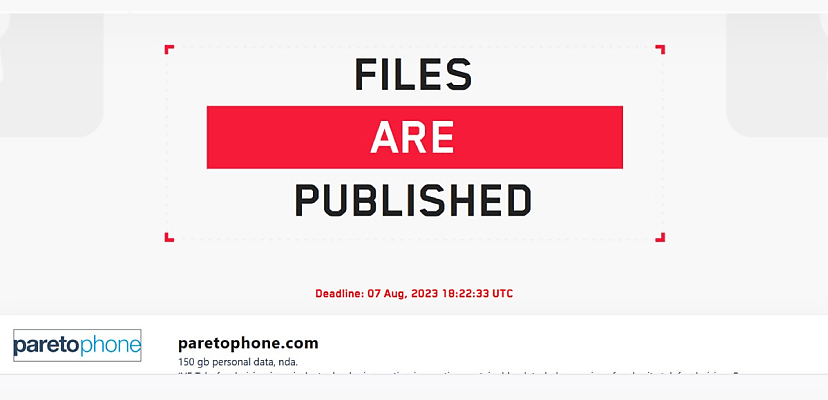

The big headlines regarding the recent Pareto Phone hack all involve the possibility of data belonging to the company’s various charity partners being leaked – but what’s actually inside LockBit’s 150 gigabyte data dump?

There’s no doubt that there’s a lot of data involved. The text file of just the file tree information alone adds up to nearly 45 megabytes and consists of hundreds of thousands of lines – each one, in theory, representing a single file.

There are Excel and Word documents, images aplenty, detailed internal information belonging to Pareto itself, and data belonging to a wide range of Australian and international charities.

And it’s across a wide timeframe, too. The earliest files date back to 2007, which raises the very important question of data retention. And forget about donor details – unless it involves losing a credit card number or other donor information, the public learning that conversions for the Cancer Council of NSW were down in a particular month pales in comparison to some of the data that Pareto was holding onto.

For instance, Pareto seems to often run criminal checks on prospective employees – and the findings for these are now on the darknet. Does this really need to be kept on file? Surely, a simple database of people knocked back for their criminal records would suffice. Keeping detailed, individual reports from the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission seems a touch overzealous.

There’s also a raft of HR data regarding Pareto employees, some of it involving staff counselling and other sensitive matters best left between an employee and their boss.

This is on top of payroll reports, leave details, tax details, and a whole mess of invoices, often linked to the charities that do business with Pareto.

And that list is extensive. Black Dog Institute, Life Flight New Zealand, Paralympics Australia, Legacy, Medecins sans Frontieres, and many, many more, all have data listed in the file tree compiled by the threat actor behind the hack, LockBit.

We’ve already had some charities, such as Bush Heritage Australia and Legacy, confirm that the details of their donors have been breached, so the big question is, does this mean every charity that Pareto does business with has been affected?

That’s a little harder to ascertain.

Data mining on the darknet

Part of the issue of working out what data has been published is that leak sites like LockBit’s are often targets for cyber attacks of their own. LockBit runs nine different mirrors of its leak site as protection against DDoS attacks, but the site was entirely unavailable for 24 hours after the attack. Even now, its mirrors continue to be regularly unavailable.

The sheer size of the data that LockBit claims to have (we’ll get back to the “claims” angle shortly) is also an issue. In many cases, once LockBit publishes the data it’s stolen, it can be downloaded with the click of a mouse. In the case of Pareto’s data, however, LockBit has chosen to host a live version of the company’s file structure on its site, where you can browse and download individual files. The site’s file browser only displays 14 lines of data at a time, and if you’re in a directory with, say, 7,427 files, that browsing is going to be slow.

Glacially slow, in fact, when you consider that Tor is bouncing your requests all over the planet. It took the better part of an hour just to browse through nearly 1,000 lines of the stolen data.

Then of course there’s the fact that there seems to be a lot of duplicate data. There are many directories and folders that, when clicked into, deliver identical results to other folders, even down to the number of files and the files themselves. According to the file structure document, there should be a folder absolutely packed with invoices from dozens of Australian charities – but finding it is another thing entirely.

There are three likely possibilities here. The first is that between the data being exfiltrated and then dumped onto the darknet, something weird happened to the data. Perhaps it’s just more file complexity than LockBit’s site can handle – though if the group is competent enough to commit such highly technical crimes at this scale, you would think that some web dev may not be beyond them.

The second option is that LockBit is padding its data. Threat actors do engage in this behaviour, making a breach seem more dire than it actually is. Which is not to say this leak is already pretty disastrous as it is – but it may not be as bad as it could be.

Of course, the third possibility is user error, and we’re just not looking in the right places. We’re not criminals, and the darknet can be weird.

Our suspicion is that there is a file structure issue on the leak site, however, which does make it hard for your average punter to pinpoint the data they may be looking for. However, a number of charities have confirmed donor data has been affected, and it does appear that Pareto is being very proactive in contacting charities that have in fact been impacted.

This is to be applauded, but there’s a large elephant in the room.

The real issue: Data retention

As we’ve said, this is a huge trove of data, some of it nearly two decades old. A lot of it is detailed, much of it involves personally identifiable information, and some of it is quite sensitive. In other words, it is very useful data for scammers and phishers, who might be able to grab the name of someone from accounts, spoof their email address, and then contact another employee to catch them in a scam.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

For many companies, Australia’s data protection laws are opt-in. Only companies that earn over a $3 million threshold, government agencies, and healthcare providers are bound to the Privacy Act 1988. Employee records are exempt since a company does need to keep such things as payroll records long-term.

And that’s just at a federal level – state laws may have other requirements. Similarly, there are different laws for different organisations. Data retention for a small business is a very different affair to, say, a telco. They both operate under very different regulatory requirements.

And different kinds of data come under different regulations, and honestly, clearer rules are required. Sarah Sloan, head of government affairs and public policy ANZ at Palo Alto, agrees.

“The leak of the personal information of Australian donors is an unfortunate outcome for everyday Australians and the charities supporting those most in need, demonstrating how low cyber criminals are willing to stoop in search of a payday,” Sloan told us via email.

“On the back of high-profile cyber attacks such as these, it is important we review and assess the effectiveness of our national cyber security policies, legislation, and cyber advisories.

“The federal government is already undertaking a review of the Privacy Act to ensure that it reflects Australia’s values and community expectations when it comes to securing personal information – including whether these obligations should apply more widely across our economy.”

There is also the issue of knowing what your partners are doing with your data. In this case, many of the charities have expressed disappointment that so much of their data was being held by Pareto for so long.

“This recent breach by telemarketing group Pareto Phone has resulted in thousands of donor data held by multiple Australian charities leaked into the dark web,” Sumit Bansal, VP Asia Pacific and Japan at BlueVoyant, also told us.

“As some charities caught up in this breach have reported, they were not aware their data was still being held by the telemarketing group.

“To help prevent breaches, organisations should know which vendors, suppliers, and other third parties have access to their data and which are critical to business continuity. Organisations should then continuously monitor their supply chain so that if any signs of weaknesses or compromise occur, they can quickly work with third parties to remediate the issue.”

To be clear, Pareto is doubtless not alone in falling foul of holding onto data in this manner. Businesses all over Australia are likely storing vast amounts of legacy data that is no longer needed, data that relates to business practices, financial details and no doubt, reams of customer and employee data.

Alarmingly, in the case of Pareto, much of the data seems to have come from the D: drive of a single machine. This begs the question: who knew this data was sitting there, relatively unsecured, and just how much was there?

This incident drives home the importance of regularly taking inventory of the data on a network, and for IT teams and company executives to be constantly aware of the impacts of the loss of that data. The damage to brand, reputation, and income from such a data breach can be immense.

This is to say nothing of the well-being of an organisation’s customers and stakeholders – already a fragile thing in the wake of a string of high-profile cyber attacks. If Australia is going to become the most cyber-secure country in the world in the coming decade, there’s a lot of work to be done.

David Hollingworth has been writing about technology for over 20 years, and has worked for a range of print and online titles in his career. He is enjoying getting to grips with cyber security, especially when it lets him talk about Lego.

Be the first to hear the latest developments in the cyber industry.